VC Dimensions¶

Infinite Hypothesis Spaces

scribble

slides

transcript

M: Howdy, Charles.

C: Howdy, Howdy.

M: Sure, why not. How’s it going?

C: How do? It’s, doing quite well. Thank you for asking.

M: Sure.

C: How’s it going on your end of the world?

M: I’m feeling okay, let’s say. Though I’m a little concerned because last time we, we were talking and you said you had a question. And I promised that I would get into it. And it’s complicated, but it’s really interesting. So, let’s remind ourselves what the question was. So, we’re talking about bounding the number of samples that we need to learn. A classifier or a concept in some given hypothesis base, h. and we ended up driving a formula that looks like this. So, the formula tells us that we’re okay, as long as the number of samples is at least as large as 1 over the air parameter, epsilon ; times the quantity log of the number of hypotheses. Plus the log of 1 over the failure parameter. And, and so if the We want to make sure that we succeed with very low failure probabilities. Delta’s very small and that means we need more samples and if we want to make sure that this error is really small, that also makes this quantity big, which means we need more samples. Right, so do you remember this?

C: I do remember this.

M: Alright and what was your concern?

C: Well my concern was that the number of depended on the size of the hypothesis space. And I was wondering what happen if you have a really, really large hypothesis space. Like for example, one of infinite size or infinite cardinality I suppose is the right term.

M: Alright well lets do a quiz.

Which Hypothesis Spaces are Infinite

scribble

K-NN is considered non parameteric.

slides

transcript

M:Okay, here’s a quiz! So, just to get at this issue of why it’s so important that we consider infinite hypothesis spaces, let’s look at some hypothesis spaces that have come up in prior lectures. So, for each one on this list check it off if it’s infinite, and otherwise don’t check it off. Does that make sense?

C: Makes sense to me.

Answer

M: Alright, what do you got?

C: Who me?

M: Yeah. So, for each one, tell me whether or not it’s infinite.

C: Okay. Linear separators they seeming like half planes, or lines, or, you know, depending upon dimensionality. There are, of course, an infinite number of these things. There are an infinite number of lines.

M: So, that, we’ll check that one off.

C: So, y equals mx plus b. And, I can put any real number for m. Any real number for b. Infinite number of those, in fact there’s not just an infinite number of those there is of those infinite numbers. We should talk about that one day. Artificial neutral networks are exactly the same thing, they have weights those weights are real numbers, so even if there were only one weight there is an infinite number Of real numbers to chose from, so that’s also the limit. Decision trees, with discrete inputs. I have two answers for you here Michael.

M: Oh!

C: Answer one is, of course, it’s finite, a, a, assuming there is only a finite number of features. The other answer is it could be infinite if I’m allowed to re-use features over and over again even if they’re useless to reuse. But that is sort of insane and silly, and no one will ever do that, so I think the, that right answer is to leave it unchecked.

M: Okay.

C: And then finally decision tree with continuous inputs. Well, that’s the same. We had a long conversation about this when we talked about decision trees. We can keep asking questions about them so if there’s a sort of an infinite number of questions you can ask. I can say, well, is this feature greater than .1. And then ask is it greater than .11. Then is it greater than .111, then .1111, then 1111111 and so on and so forth. So, that is also infinite.

M: So basically everything we’ve talked about, or nearly everything we’ve talked about actually doesn’t fit the analysis that we talked about last time.

C: What about k and n?

M: Yeah so k and n is a little bit of a mess. I think you and I maybe don’t completely agree on this one. So I think of k and n, the classifier that comes out of a k and n is defined by the set of data points that are the, the neighbors.

C: Mm-hm.

M: And. There’s an infinite number of ways of laying out those points. So there’s an infinite number of different tan N base classifiers that you could have. But you have a counter argument to that.

C: Right, which is that if you assume the training set is fixed. And that’s just part of the parameters of the hypothesis base then. It is an infinite. There’s, in fact, only one. It all just depends upon

Q. And it always gives you the same answer, no matter what. So I think the hypothesis space, you could argue, is finite. It all depends upon what it is you’re taking as part of the hypothesis. And what it is you aren’t taking as part of the hypothesis space.

M: Right. Sort of, whether the data is built in or not. It strikes me that these other methods are also similar in that, if you bake in the data, there’s just the one answer. But yeah it’s a, k and n is weird. Right? Because it’s sometimes called non-parametric.

C: Right.

M: Which sounds like it should mean that it has no parameters but what it actually means that it has an infinite number of parameters.

C: Right. By the way, I don’t think that’s true about baking things in. So, for example, if I give you a set of data. There’s still an infinite number of neural-networks that are consistent with that data. There’s a whole bunch of decision trees that are consistent with that data. So you don’t always get the same answer every time. Certainly with neural-networks you don’t because you’re starting at a random place.

M: But it, but if you, right. If you’re bake in the algorithm and the data and I think in k and n that is exactly what you’re doing. But I agree that we can agree to not agree.

C: Agreed.

May be It Is Not So Bad.

scribble

slides

transcript

M: So here’s an example to explain why maybe the situation’s not so bad after all. So let’s look at a particular example. We’ve got our input space consisting of say, the first 10 integers. And our hypothesis space is, you take an input, and then you just return whether it’s greater than or equal to some theta. So that’s a parameter. And now, how big is the hypothesis space?

C: What type is data?

M: Let’s say theta’s a real number.

C: Oh, so it’s infinite. Infinite!

M: Indeed it is. Now, on the other hand, what would you do to try to learn this? Can you use the algorithm that we talked about before to learn in this particular space? So, I guess what I’m asking is, is there a way you can sort of sneakily apply the ideas from before, now the ideas from before were that you actually keep track of all the hypotheses. And to keep the version space, and once you’ve seen enough examples that are randomly drawn, you would be able to know that you’ve epsilon-exhausted the version space, and then, ultimately, any hypothesis that’s left is going to be okay. So, what could we possibly do to track all of these hypotheses? It’s problematic, because there’s an infinite number of them.

C: Okay. I see where you’re going with this. So when I asked you what type it was, you said it was a real number, but it would have been easier if it, theta weren’t a real number, but were in fact, you know, a positive integer say, or a non-negative integer.

M: That’s true, though there’s still an infinite number of those.

C: True, but it doesn’t matter because the size of X is, it’s so finite. So any value of theta greater than ten for example It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter because it will always give you the same answer.

M: Alright. So if we, what if we only track the non-negative integers 10 or below. This would be, what, it’s finite. And it gives us the same answer, as if we had actually tracked the, the infinite hypothesis space. So there’s kind of, well, I dunno, you had a, you had a good way of saying it before, do you want to say it again? What is the difference between kind of this hypothesis space that we’re working with, and the hypothesis space as we defined it?

C: So there’s a notion of syntactic hypothesis space which is all the things you could possibly write, and then there’s the semantic hypothesis space which are the actual different functions that you are practically represented.

M: Yeah, I like that, that, that you can make a distinction between semantically, say, finite hypothesis base and actually, it specified syntactically infinitely. And you also have the example of of a decision tree. With discrete inputs as also being kind of like this. That we, you know, we, generally think about only ones that split on a attribute once, but syntactically you could keep splitting on it. It just doesn’t give you a semantically different tree. So, this is kind of at the heart of what we’re going to be able to do to talk about how we can learn and if in an hypothesis space, more complicated ones than this example here. But at the same time, without having to track an infinite number of hypothesis, because there’s just not that many that are meaningfully different.

C: I like that.

Power of Hypothesis Space

scribble

slides

transcript

M: So, this is how we’re going to be able to measure the power of a hypothesis space. This is a really clever definition. I did not come up with this and it goes like this. For a given input and hypothesis space, we’re going to ask what is the largest set of inputs that the hypothesis class can label in all possible ways? So, in this example that we were looking at, it’s actually really simple because it turns out the answer is one. so, here, here’s an example. So being able to do this with one is not such a big deal. If S is a set of points, a set of inputs, in this case just six, it’s one of the inputs from the set. Then are there hypotheses in the hypothesis class that can label this in all possible ways? Well, there’s only two possible ways. It can label it as true and it can label it as false. So, here if we set theta to I don’t know, five, it’ll label it as true. If we have a different hypothesis that say sets theta to eight, then we can label it as false. There is a set of inputs of size one that we can label in all possible ways. But is there any pair of inputs that we can label in all four ways?

C: I’m going to say no.

M: And why is that?

C: Well because you’re writing it, you’re writing it in sets but I sort of think of these as points on a number line, and theta as a separating line. And there’s just kind of no way to label anything to the left of the line as negative, ever. Because you’re requiring that x is greater than equal to theta to be positive, so you can never label anything to the left of that line as negative. So all I have to do, right, is make x1 negative and x2 positive, and there’s nothing you can do. Is that right?

M: Indeed it is. So, in particular, pick any two points x1, x2 on the line just like you said, if as we roll theta, if we just kind of consider sets of theta as moving from left to right, it starts off where x1 and x2 are both going to be labeled as true. Then as we move theta to the right, x1 is going to eventually start to be labeled false, so that okay, that’s now two of the combinations we’ve seen. We’re going to keep moving theta to the right, and now x2 is labeled as false. So we’ve seen three of the combinations, but which combination didn’t we see?

C: true, false.

M: And there’s just no way to make that happen. Just like you said.

kC: So would you say this is a weak hypothesis space?

M: It definitely seems to be pretty weak, even though it’s infinite. In fact, did it depend on x being finite?

C: No, actually, it didn’t. You’re right.

M: Yeah, so all, so this really applies in the, in this very general setting. We can take this definition, bring it to bear on an input hypothesis pair like this, and it gives us a sense of how expressive or how powerful the hypothesis space is. And in this case, not very expressive.

What Does VC Stand for?

scribble

Labelling in all possible ways is termed as “shattering”.

What is the largest set of inputs that the hypothesis class can label in all possible ways? - This is called as VC dimension.

VC Dimension of a class can be related to amount of data needed to learn about that class.

slides

transcript

M: So this is a concept that we’re going to be able to apply in lots of different settings when we have infinite hypothesis classes. And this is really the fundamental way that it’s used except usually, there’s kind of a more of a technical sounding definition. This notion of labeling in all possible ways is usually termed shattering. So this quantity that we’re talking about here, this, this size of the largest set of inputs that the hypothesis space can shatter, is called the VC dimension.

C: What does VC stand for?

M: VC stands for Vapnik - Chervonenkis which is a pair of actual people. So that, you know, really smart insightful guys that put together this notion of a definition and what they did is they can relate the VC dimension of a class to the amount of data that you need to be able to learn effectively in that class. S, as long as this dimensionality is finite. Even if the hypothesis class is infinite. We are going to be able to say things about how much data we need to learn. So, that’s, that’s really cool. It really connects things up beautifully. So, I think what would be a really useful exercise now is to look at various kinds of hypothesis classes. And for us to measure the VC dimension.

C: Okay, sounds like fun.

Quiz: Internal Thinking

scribble

slides

transcript

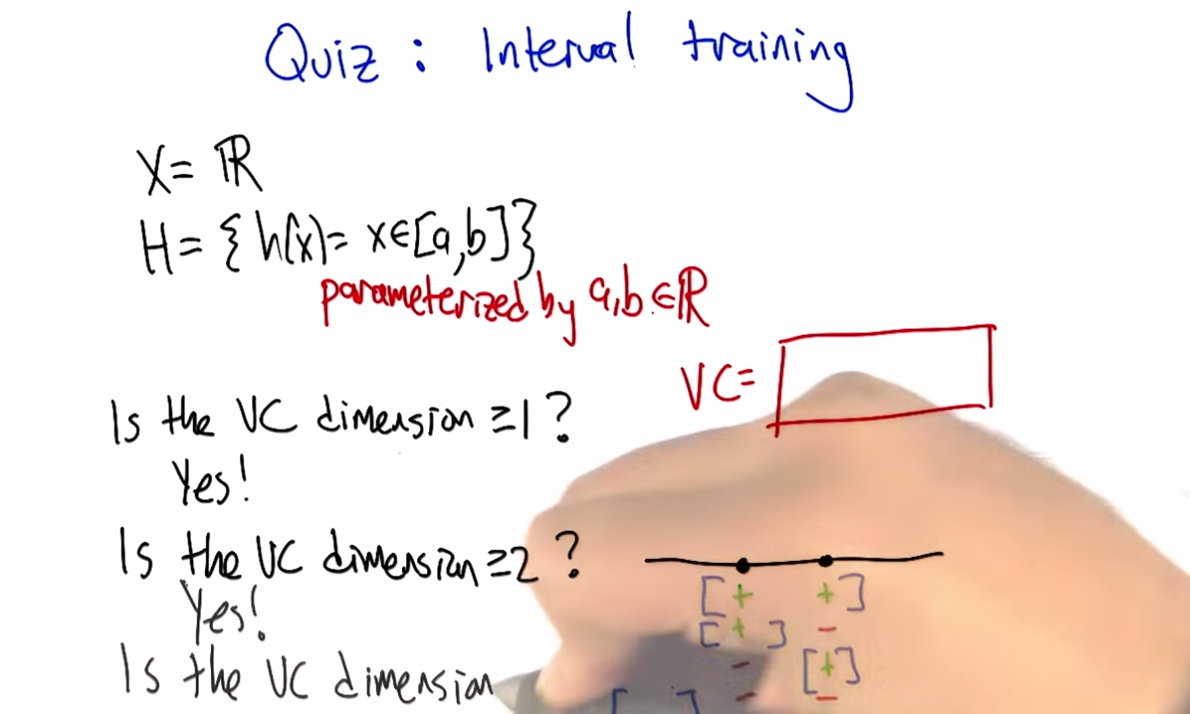

M: So let’s look at a concrete example, where the hypothesis space is the set of intervals. So the inputs that we are trying to learn about are just single numbers on the real line. And the hypothesis space is this set of functions that return true for all the things that are between a and b, and this is parameterized by a and b. So how many different hypotheses are there in our class here?

C: At least 2.

M: Sure. How about how many are there in the class?

C: There’s an infinite number of them.

M: That’s right. So, so this is one of these situations where it’s going to be really helpful to apply the notion of VC dimension if we think we’d like to be able to learn from a finite set of data. Which, you know, generally we like that. So how do we figure out what the VC dimension is? We want to know, what is the largest set of inputs that we can label in all possible ways, using hypotheses from H. Alright, so, I want you to figure that out. Figure out the size of the largest set that we can shatter, that we can label in all possible ways using these hypotheses. And then just, you know, write it as an integer in this box.

C: Cool.

Answer

kM: OK, so how do we figure this out?

C: Cleverly, so I, when I, when I see things like this, I just like to be methodical, so why don’t we just be methodical so, I’m going to ask the question whether the vc dimension is at least one, because it’s pretty easy to think about and maybe I’ll get a feel for how to get the right answer that way. OK, so is the vs dimension at least one? Well, the answer is pretty clearly yes, so if you just put a dot on the number line somewhere. You could label it positive just by picking any a less than or equal to that point and any b greater than or equal to that point. So, if, if I were like drawing parentheses or something to indicate the interval, I could just put parenthesis around the point and that will give me a plus or brackets, that would be fine. Okay, so that’s that’s pretty easy. And if I wanted it to be negative, I could just put both of the brackets on either side of the point, it doesn’t matter, let’s say to the left. Alright, that make sense Michael?

M: That’s exactly what I was thinking about, yeah. Though I would’ve put the brackets on the right.

C: Yeah, you would. okay, so then we could see…do the same argument for, see if the VC dimension is greater than or equal to two. So if I put two points on the line, so there are only,there’re four possibilities I gotta get. Plus plus, minus plus, plus minus, and minus minus. Okay, so we gotta get plus plus, plus minus, minus plus and minus minus. So, the, the first and the last one are really easy. Actually they’re all easy but you can definitely do this. So, if you want to get plus plus, you just need to put brackets so that they surround the two points, that’s good. If you want to get plus minus you put the left bracket in the same place and you put the right bracket just to the right of the point, yeah, and you do the same thing for minus plus and then for minus minus you put the brackets on either side of both of the points and so, since you like it to the right I’m going to put em to the left.

M: [LAUGH] Good.

C: And there you go, that was, that was pretty easy I think. Okay so next we need to figure out whether the VC dimensions at least three. So we need three dots on a line, three, distinct dots on a line. And we’ve got eight possibilities but Michael I don’t want you to write down those, those eight possibilities because I think I see an easy way to answer the question right away.

M: Excellent

C: So, this is a lot like the last example we did with, with the theta. Except now.

M: Yeah.

C: We only have two parameters. And the problem with had with the theta was that as we moved the theta over, from left to right, we lost the ability to, to, to have a, a, a positive followed by a, a negative. So I think there’s a similar thing here. So, if you label those three points this way. Plus, minus, and plus. I don’t, I don’t think you can do that, and that’s because in order to get point one and point three in the interval, you’re going to have to put the brackets on both sides of them. So you’re going to have to put a, a left bracket to the left of the first point and a right bracket to the right of the third point. And that’s the only way to make those two plus. But then you’re always going to capture the one in the middle. So you can’t actually shatter three points, with this hypothesis class.

M: Now, you have to argue though, that there isn’t some other way you could arrange the three points. I don’t know like, I don’t know, stacking them on top of each other or something.

C: You mean vertically on top of one each other?

M: Yeah.

C: Well then they wouldn’t be in R, they’d be in R2.

M: Well no, just like right on top of each other.

C: Well then they’re all the same point.

M: And you can’t label them. Again, you have the same problem that you can’t label one of them negative and the other ones positive if they’re all on top of each other.

C: Right.

M: So, so there isn’t, there just isn’t any way to set up these three points so that you’re able to assign them all possible labels.

C: Right.

M: So, good, so that gives us two as our answer here. So, by the way, I think that you said something I think that’s really important. In order to prove the lower bound, in order to prove one and two, all we had to do was come up with an example where we could shatter, right?

C: Yes, that’s exactly right.

M: Right, so so that’s good and that’s that’s really nice because otherwise we’re in a heap of trouble [LAUGH] if we have to show that you can shatter every single thing. We just have to show that you can shatter one thing. So, it exists. So that whole VC dimension is really a…there exists some set of points you can shatter, not you can shatter everything.

C: That’s right, and what would be an example of points that you couldn’t shatter yeah, a pair of points that you couldn’t shatter?

M: Well, the ones on top of one another.

C: Yeah, exactly, because you wouldn’t be able to assign them different labels.

M: Right.

C: So that would be a really bad choice, and here all we need is a good choice.

M: Right. So, if you make good choices you can shatter things, which sounds more violent than I intended. Okay but, in the third case of the VC dimension, it wasn’t enough to show an example that you couldn’t shatter, because, then you could do the same thing as you point out, with a VC dimension of two. Instead you have to prove that no example exists. So, there does not exist or a for all not word or something.

C: For all, not.

M: [LAUGH] Exactly. So, that, that’s a, that’s an interesting set of set of requirements there, right? So, proving a lower bound seems easier than proving an upper bound.

C: Though it’s interesting because in this case, in cases one and two, you had to show that all the different combinations were covered, whereas in this last case we just had to give one combination that couldn’t possibly be covered.

M: Yeah, but it couldn’t possibly be covered no matter what we did. No matter what the input arrangement was.

C: Right.

M: Yeah.

C: Whereas in the first case, I had to show all possibilities. I mean, you know, all possible labelings but only for one example of orderings or one collection of points. So just messily doing some bad predicate calculus to, nail down what you’re saying. That when we say that the answer is yes, we’re saying that there exists a set of points of a certain size, since that for all labelings, no matter how we, we want to label it. There is some hypothesis that works for that labeling. But to say no, we have to do the legation of that which is not exist for all exist. Which, by standard logic rules says that, that means for all points, no matter how you arrange the points, it’s not the case that for all labels. There exists hypothesis which again DeMorgan’s Law its not against DeMorgan’s Law to to apply this idea that says that’s the same as for all arrangements of points there’s some labeling where there’s no hypothesis that’s going to work and that’s exactly how you made your argument.

M: Huh, except I didn’t use DeMorgan’s Law and upside down a’s and backwards z’s. Oh you did, oh you did.

Quiz: Linear Separators

scribble

slides

transcript

Quiz: Linear Separators

M: Alright, let’s do another quiz. That previous example that we looked at of intervals, was nice and pedagogical, and reasonable to think about, but we actually hadn’t really talked about any learning algorithms that used intervals. On the other hand, linear separators are a very big deal in machine learning. So, it’s, it’s very worthwhile, and it turns out to be not too bad to work out what the vc dimension is for linear separators. So, let’s say that we’re in two dimensional space, and so our hypotheses have the form that you’ve got a parameter, a weight parameter, w. And were going to just take that weight parameter, take the dot product with whatever the input is, and see whether its greater than or equal to some value, theta. And if it is, then we say that’s a positive example, and if not it’s a negative example, and geometrically that just means that we’ve, we end up specifying a line, and everything on one side of the line is going to be positive, and everything on the other side of the line’s going to be negative.

C: Got it. That makes sense. So what’s the vc dimension? Oh, they’re going to have to tell us. I like that.

M: Alright.

Answer

M: Alright so we’re back in again, and we’re going to attack it I the way that we, that you attacked the previous ones, where we’re going to ask, kind of systematically is the VC dimension, greater than or equal to 1, 2, 3, 4 by, by giving examples until we just can’t anymore [LAUGH]. So good, so is the VC greater than or equal to one?

C: Yes.

M: Yes. So, what would that mean? All we need to do is provide a point, I don’t know, call it the origin. And.

C: Basically, we get to just pretend that it’s like a single point on a line with a VC dimension of one and it, the same argument that we had before, applies.

M: That’s a good way to say it. Just you know, just think about the x asis, axis itself, and we can label something, well actually it’s simpler in a sense because, we can keep the line steady and we can just flip which side is, you know, by negating all the weights we can flip which side is positive and which side is negative, and that gives us the 2 labelings of that point.

C: Right, and because similar argument for VC of 2.

M: So, if the 2 points were on a line, then to do the 4 different combinations, we could.

C: So right, by putting that line to the left, we can label both of them positive. That’s easy, or we could label both of them negative by flipping the weights. Now we’ve to do the other 2 cases where they’ve different labels. So, I’m going to recommend putting a blue line between them.

M: It’s a thin blue line.

C: [LAUGH] Yes, and you know, the one on the right is positive the one on the left is negative, or we can flip the weights and then flip the signs.

M: Yes, and 3 is where we got into trouble last time, so let’s let me start off by giving ourselves a clean slate. So, this ran us into trouble in the case of the intervals because we couldn’t do that case an it looks like we’re kind of hosed again, right?

C: Yeah, we’re. We’re actually completely hosed again, if we do this.

M: [LAUGH]

C: So, I’m going to say that the problem is not with the hypothesis space. The problem is with the hand that is drawing points on the screen. So that’s you, so here’s the.

M: My hand is really depressed.

C: Well, I’m going to make your hand happier. So, I think it’s right that you can’t separate this. It’s, and, and the reason you can’t separate it’s because we’ve sort of nothing to do here, just like we’d before. But, we are not restricted to the number line. So I’m going to recommend cheating, and moving that point in the middle off the number line. So make a triangle, stick it up in the middle somewhere.

M: Alright, and that gives us the ability to handle this case now, because we can just send our slicey line this way. Put everything below it as positive and everything above it as negative.

C: Right, now of course we still, by doing that we might have messed up the other labeling, so we should check to make certain that we haven’t we haven’t screwed anything up. So, we can, we can make the top minus and the bottom, plus that’s true and we can just by flipping the weights we can make it the top plus and the bottom minus right? So that’s good. And the question is that can we do anything else.

M: Yeah, I think it’s pretty clear. We could definitely label them all positive or all negative just by putting a vertical line somewhere off to the left.

C: Yeah, and I think it’s actually easier than this because if you just think about vertical lines, then we really are back in the one dimensional case.

M: Right. And, and we handled the other 7 cases in the one dimmensional case really easily. It was just this, this extra case that we didn’t know how to do and now we do, we just use that 3rd dimmension. [LAUGH] Or the 2nd dimmension, even better.

C: Fair enough. Okay, so the answer’s yes. I feel good about that. Okay, so, that’s good. So we got, we got 1, 2, and 3 out of the way, so we know it’s more powerful. We know that it’s better. This’s, this’s kind of nice. So now the question is 4. So, thinking about it, I think that the answer is no.

M: [LAUGH] That would be nice, wouldn’t it? But, no, we need a, we need a slightly better argument and I think, I think we can do that, what we need. Again, what would be helpful is if we had an example, where we could say, okay, here’s a labeling that no matter how you lay out the points, you’re going to fail.

C: So, in order for that to work, we need to try to use all the power of the 2 dimensions so we don’t fall in a trap. Right if, like we almost did with VC3 by making them collinear. So, why don’t you place 4 points in the plane and make a kind of like a diamond shape, or a square, which is like a diamond.

M: It’s a diamond shape if you yeah, tilt your head a little bit.

C: Okay, so I’m going to tilt my head to look at it. So, here’s my argument. Now, I don’t know if this is quite right Michael, so, so help me out with it. The reason I don’t think you can do 4 is because we’ve only got lines to work with. Okay so, if you connect all the points [CROSSTALK]

M: Hm-mm.

C: All, all pairs of points the way they, all ways they can be connected. So, you know, draw the square on the outside and then draw the 2

M: Hm-mm.

C: Cross ones in the middle. Does that make sense?

M: Yeah, it makes sense, but I’m not sure where we’re going with this.

C: Okay, so I’m not either so [LAUGH] so, so, so work with me. So that’s kind of all the boundaries that you can imagine drawing. And the problem that I see here is that because of the way that the, the 2 lines that the x and the interior of the square’s set up. There’s kind of no way to label the ones on the other side of those lines differently without crossing them. So that made no sense what I said, right? So, try putting the, a plus in the upper left and bottom right. And minus for the other 2. So, if you look at the, the 2 1’s that are connected by the line with the plus, and the 2 right? There’s no way to put a single line that will allow you to separate out the pluses from the minuses here.

M: Yeah, yeah. Exactly. So, in particular anything that puts, these 2 pluses on the same side is either going to put one minus or the other minus on that same side.

C: Right.

M: It has a very XOR kind of feeling to it, to me.

C: Yeah does, it, it,it does and in fact it has an x right there in the middle.

M: [LAUGH] It does, no but it, that is true, but I meant it in a slightly different way, which is if you think about these 4 points as actually being you know, zero, zero. 1-1, 0-1 and 1-0.

C: Mm-hm.

M: Then, the labeling here is exactly XOR. And XOR is one of these things that you can’t capture with a linear separator. So I think, I think you got it.

C: Oh, it makes sense. And I think the important thing here, is that oh I like the XOR argument. The important thing here is that, no matter where I move those four points, I can take the one closer or one further away. And I could, they’re no longer squares, but whatever I want to be, they’re always, you’re always going to have a structure where you can draw those kind of crosses between the 4 points. Or, you’re going to end up collapsing the points on top of one another or making 3 of them co-linear or all four of them co-linear and so that makes it even harder to do any kind of separation. Cause now we’re back.

M: Right. You fail on all the, but there, there’s one case that I’m not sure that you quite described yet. Like that.

C: Right. Well, I think that, that works out to be the same thing, right? If you draw the connecting lines together they’re all going to cross at the middle point.

M: There’s no crossings.

C: They all cross at that point. They all meet at that point.

M: They don’t cross at that point.

C: Well, so those are line segments, but those are just line segments they represent lines that go on forever. Good point.

M: Yeah so, but the way, the way that I would see this one is, again to just give an example of a labeling that just can’t be separated would be this one. Like if you capture the outside points, assigning all the outside points one label, you can’t assign the input, the inside points a different label. It’s inside the convex hall, it’s going to have the same label as the other ones.

C: Exactly. So, the, and I, and well so in my head the, the main issue is as lines, when lines cross there’s really nothing you can do with a single line. Never cross the streams.

M: [LAUGH] Yeah. It still doesn’t feel like quite the same. I mean maybe we’re belaboring this point. Here in this square, if you actually let this, this corner point pushed into the middle, then we can, I think we can linearly separate them.

C: Sure.

M: So, I feel like these are 2 different cases, but regardless the point is, that what we, what we argue is no matter how you lay out the points, there’s always going to be a labeling that can’t be achieved in the hypothesis class.

C: Yeah, the whole crossing of the lines thing, really is about being able to get all 4 points. It’s not saying that any pair of points. Works out okay. So, what you’d end up doing is taking one of those points and dragging them into the middle, and then the lines all meet like in, in what you’ve drawn. And you end up with the basically the, the same argument. I think it’s the same thing. But, I do agree with one thing, Michael. Which is that we are belaboring this point.

M: Because the good news or the, the exciting news is no, we really argued that the VC dimension of linear separators is not greater than or equal to four. So therefore, it’s 3. Because 3 works and 4 doesn’t.

C: And 3 is my favorite number. So, I have a question for you Michael, I noticed that we keep getting in all the examples we have done so far, we keep getting one more VC dimension, so does this kind of argument work if I went from planes to, or lets see, 2D space or 3D space or dimension still three or does it keep getting bigger?

The Ring

scribble

slides

transcript

M: Alright, so let me try to, to write that down in a, in a way that let’s us summarize it. So I think what you’re trying to say is when we did that one dimensional case, it had, the b c dimension was one. When we did the interval, it was two. When we did two dimensional, linear separator, it was three. And you’re wondering whether in, three dimensions, it would be four.

C: Yes.

M: So that’s, yeah, a really good insight. Let me, be a little bit more precise here. That the hypothesis spaces in each of these cases here, they, they were defined this parameter theta. In the interval case it was defined by a and b. In the two dimensional case it was defined by w and theta, and w was in two dimensions so this was actually, a vector of size two. So, yeah, each time we went up, it, to do a different example, we actually added another parameter. And, it looks like the bc dimension is the number of parameters.

C: Hm.

M: So in a sense it’s it’s the dimensionality of the space in which the hypotheses live. So it really, it really fits very nicely. That doesn’t exactly answer your question. It is the case that for a three dimensional problem there’s going to be four dimensions. And so it turns out you are right. That for any d dimensional hyperplane concept class or hypothesis class, the vc dimension is going to end up being d plus 1.

C: Oh, I see, and that’s because the number of parameters that you need to represent a d dimensional hyperplane is in fact, d plus 1.

M: That’s right. Yeah, d, the weights for each of the dimensions plus the theta, you know, the greater than or equal to thing.

Quiz: Polygons

scribble

slides

transcript

C: So, Michael, I know we said that was the last quiz but I think we should do one more quiz. So the quiz is going to be on convex polygons. And X is going to be an R squared. And the hypothesis is going to be points inside some convex polygon. And, and inside means the same thing as we meant with circles. So, if you’re on the polygon or on the perimeter of the polygon, then you’re inside the polygon for the purpose of this discussion. So, here’s my question to you Michael. What is the VC dimension of convex polygons?

M: Well, if I had to.

C: Ask someone else, you would say it was a quiz and you’d let them do it.

M: Is this a quiz? Oh, it’s a quiz for me.

C: Well, I dunno, do you want to let the students get a, get a try?

M: Well, yeah, and then we can answer it by simply going to the quiz if we actually go to the quiz

C: [LAUGH] Okay, so let’s go to a quiz. Go.

Answer

M: If I had to guess, which you are kind of making me do, I would say, well, for one thing, the number of parameters is infinite. Right? Because if it’s some convex polygon, and we’re not putting any bound on the number of sides on that polygon, then to specify it, you have to give what the points are for each of the vertices and the, you know, as the number of sides grows, the number of parameters grows. So it’s, it’s unbounded. So it could be that the vc dimensions is going to end up being unbounded but they do seem you know at the limit they turn into circles and circles ended up being a vc dimensions of three so maybe, you know, maybe it’s three.

C: Maybe. So, so actually you, you, you’ve really sort of stumbled on the right answer there, or maybe not so stumbled, on, on to the answer there. So, in the limit, convex polygons become circles. Right? So draw a circle for me, okay, now, lets sort of try to do this smartly, so put a point on the edge of the circle, yeah I like how you placed that, so pretty clearly you could come up with a convex polygon that puts that either in or outside of it right? Because you know, there is only one point, thats pretty easy.

M: Yeah, and the circle is kind of irrelevant.

C: Yeah the circle is kind of irrelevant, but its going to be part of my little trick. So put another point on the circle somewhere. And in the same way we’ve been doing it before with lines, you know, you can put both of the inside a convex polygon or outside, you know, you can do all the labels. I think that’s pretty easy to see. Now try three. So, the first thing I want you to notice Michael, is that if I look at those three points and I connected them together, what do I get?

M: Oh a triangle!

C: I get a triangle which is by the way, it starts with a C.

M: [LAUGH] A sheep that has the number of vertices equal to your favorite number.

C: That’s right. But it’s also a kind of geometric shape, it starts with an A.

M: It starts with a

C: It starts with AC?

M: Appaplectic.

C: No it starts with a C. AC, Accenuated. No it starts with the letter C.

M: Oh. Convex.

C: Yes. It’s actually convex polygon. Try putting a fourth point on there. And in fact put the fifth point. And a sixth point. Now, here’s my question. We’ve put all of these points on this circle, right? Now let’s just say it’s a unicircle because it’s easy to think about it. So we put all these points on the circle. Do you think we could shatter this with a convex polygon?

M: To shatter it? Right, to give it all possible labellings. Well, let me draw the polygon. So each one being in or out.

C: Well, the thing is, the way you’ve drawn this polygon, all of them are in. So, if you used this polygon, what would you be labeling those six points?

M: All positive.

C: All positive. What if I didn’t want you to label one of the points positive? Pick one of the points. Any point will do. So if I don’t want that to be in the polygon, what do I have to do?

M: Just push the, the corresponding vertex a little bit inside.

C: Right. And the easiest way to do that would be not to have a vertex there at all but simply not to connect that point.

M: Oh. It’s kind of like a, a rubber band art or string art if we just kind of pop that one out. [NOISE]

C: Right. So, any point you’d, of those six points you don’t want to be labeled positive. Just don’t connect in as a part of your polygon.

M: I see. So, for any given pattern or subset, which is what we need to be able to show, that, you know, when we’re shattering, we need to show that no matter what the subset is, there’s going to be some. Hypothesis that labels it appropriately. You’re saying, well just, you know, label the points as plus and minus, and connect up the pluses. It’s going to leave the minuses outside because they’re going to be on the edge of the circle. And the pluses are all going to be in the polygon because they touch the edges of it.

C: Yeah, because they are in fact the vertices. And in this case you just think of the fact that if there’s only two positive points a line is a very, very simple convex polygon and if there’s only one point, then a point is a very simple convex polygon.

M: So the VC dimension is six!

C: No! So what happens if I had seven points? Could I do it?

M: So the VC dimension is seven!

C: What if I had eight points? Could I do it? It’s the same trick. We can make it eight.

M: So, can we make it nine?

C: No.

M: Yes.

C: Yes.

M: So, at what point can we stop?

C: When we run out of tape for the recording.

M: Exactly. So that means that the number of points that we can capture this way is in fact unbounded. Which means the VC dimension is infinite.

C: Nice example.

M: Now, I do want to point out that there’s a, a teensy tiny little point here that, that we sort of skipped over, but I can explain in five seconds, which is we made polygons. We didn’t actually argue that they were convex, but they are convex, because they’re all inside the unit circle, and by construction, every, any polygon whose vertices are on the unit circle will be convex. So it’s just that’s why we needed a circle, that’s why we were being clever with it, but there you go. So we have a polygon that we can always draw with those the right thing and because its always subtended by it’s circle it will be convex. So we have actually found a vc dimension that’s infinite [CROSSTALK]. Or a hypothesis class that has a vc dimension. [CROSSTALK] It has to be infinite, yeah that’s what I said. We have actually found the hypothesis class whose vc dimension is infinite and we came up with a proof where why would be that case, and nicely, I think very nicely connects with the observation you made earlier. That, somehow, it connects with the number parameters. I think it’s kind of cool. I mean, you, you, end up with a circle, not having a very good VC dimension, a very high VC dimension, but convex polygons, which somehow seem not to be as cool as circles, are in fact, in fact have infinite VC dimension. Okay so there you go so we’ve done some practice of VC dimensions. So you’ve given me all this VC dimension stuff, I agree that it’s cool Michael, but what does it have to do with, what we started out this conversation with? How does that answer my question about the natural log of an infinite hypothesis space?

Sample Complexity

scribble

slides

transcript

M: That is exactly the right question to ask. It’s fun to spend all day finding the VC dimension in various hypothesis classes. But that is not why we are here. The reason we’re, why we’re here is to use that insight about VC dimension to connect it up with sample complexity. And so here is the equation that you get. When you connect these things up. It turns out that if you have a sample set the, the size of your trading data, is at least as big as this lovely expression here. Then that will be sufficient to get epsilon error, or less, with probability 1 minus delta. And so, the form of this looks a lot like how things looked in the finite case. But, in fact it’s a little bit weirder.

So 1 over epsilon times quantity eight times the VC dimension of H. So that’s where this quantity is coming into play. So the VC dimension gets bigger, we’re going to need more data. Times the log base 2 of 13 over epsilon. Sure. Plus 4 times the log base 2 of 2 over delta. So, again, this log of, of something like 1 over delta to the inverse of delta, was in the other bound, as well, that’s capturing how certain we need to be that, that things are going to work. And again, as, as delta gets small, the failure probability gets small. This quantity gets bigger. And the num, and the size of sample needs to be bigger. But, but this is the cool thing. That the VC invention is coming in here in this nice, fairly linear way.

C: So it sort of plays the same role as the natural log of the size of the hypothesis space.

M: Yes, that’s exactly right! And in fact, things, things actually map out pretty similarly in the finite case and the infinite case. That there’s an additive term having to do with the failure probability. There’s a, you know, one over epsilon in the front of it and then this quantity here, having to do with the hypothesis space, is either the size of the hypothesis space or the dimension of it, depending. Well the size here is logged and the VC dimension is not, so that’s a little bit of a difference.

C: Mm.

M: But but there’s a good reason for that as it turns out.

C: There is?

M: Yes, indeed. So why we, why don’t we take a moment and look to see what is the VC dimension of a finite hypothesis class? The VC dimension concept doesn’t require that it’s continuous. It’s just that when it’s continuous, the VC dimension is required. So that maybe that’s a useful exercise. Let’s do that.

VC Dimension of finite Hypothesis

scribble

Hypothesis H is PAC Learnable if and only if VC dimension is finite.

slides

transcript

M: So we can actually work out what the VC dimension of a finite H is and, in fact, it’s easier to just think about it in terms of an upper bound. So, let’s, let’s imagine that the VC dimension of H is some number, D. And the thing to realize from that, is that, that implies that there has to be at least two to the d distinct concepts. Why is that? Is because each of the two to the d different labelings is going to be captured by a distinct hypothesis in the class, because if we can’t use the same hypothesis to get two different labelings. So that means that the, that two to the d is going to be less than or equal to the number of hypotheses. It could be that there’s more, but there can’t be any fewer, otherwise we wouldn’t be able to get things shattered. So, just you know, simple manipulation here, gives us that d is less than or equal to the log base 2 of h, so there is this logarithmic relationship, between the size of a finite hypothesis class. And the VC dimension of it, and again, that’s what we were seeing in the other direction as well, that the, that the log of the hypo, size of the hypothesis space was kind of playing the role of the VC dimension in, in the bound. Okay, that makes sense. And, and from that, it’s easy to see how 13 got in there.

C: Yes. It should be pretty much obvious to even the most casual observer of 13.

M: Yes, I think that’s right. So I don’t think there’s any reason for us to explain it.

C: Yeah, I think one would have to really go back and look at the, at the proof to get the details of why the, it has the form that it has, but, or at least the details of the form. The, the, the, overall structure of the form, I think we understand. It’s just that the details come out of the proof and we’re not going to go through the proof.

M: And I think that’s probably best for everyone.

C: So what, what we’re seeing at the moment is that a finite hypothesis class or a finite VC dimension, give us finite bounds, and therefore make things PAC-learnable. What’s kind of amazing though is that there’s a general theorem that says, in general, if H is PAC-learnable if and only if the VC dimension is finite. So that means that, we know that anything that has finite VC dimension is learnable from the previous bound. But we’re saying that it’s actually the other way as well, that if something is learnable it has finite VC dimension. Or to say it another way, if it has infinite VC dimension, you can’t learn it. VC dimension captures, in one quantity, the notion of PAC-learnability, which is, which is really beautiful.

M: Yeah, I agree. That V and that C guy, they’re pretty smart.

Summary

scribble

slides

transcript

VC Dimension

Shattering

Relationship between VC Dimension and true number of parameters.

VC relates to size of hypothesis space.

How to compute VC dimension.

PAC Learnability.